Wednesday, January 2, 2013

Time-lapse photography with drone parts

Let’s say you’re a journalist and you want to record an important event taking place over an extended period, say 12 to 72 hours. Or even a week, or longer. If you want to record the event with video, that’s far too long to expect anyone to watch it in its entirety.

You can, however, record the whole thing and use some kind of time compression in post-production software. But if you’re recording on high definition video, you can only expect to record about four hours on a 32 gigabyte SD card. Even if you manage to capture 12 or 72 hours of high-definition video using a hard drive, it’s going to be hard to work with such a big file.

The solution is time-lapse photography, which simply means taking photos at regular intervals and turning them into individual frames on a video. During hurricane Sandy, a number of news sites and tech-savvy citizens used a time-lapse photography to document the storm's impact on New York City (below). If you’re not in a hurricane-prone area, you can find other weather-related applications for this technique, such as recording a flood-prone area during a storm.

Of course, you could just as easily record important non-weather events, such as big construction projects, or traffic on a bottlenecked road. Compressing these large-scale but slow-moving events into a one or two-minute clip makes for dramatic video.

At its most basic, you only need two things to pull off a time-lapse video. You’ll at least need a camera equipped with an intervalmeter (a fancy way of saying it can be programmed to take photos at regular intervals), and software to turn the photos into videos.

A camera battery will only last so long, though. If you’re hoping to capture an event longer than three hours, you’ll probably have to rig up an external power supply. This power supply can be as simple as a motorcycle battery hooked up to a voltage regulator, or it can be a sophisticated, computer-controlled lithium polymer setup with photovoltaic (solar) cells. Then there’s the matter of finding a memory card of sufficient size, and a mounting solution with sufficient stability.

Simple is better. If you’ve got drone journalism equipment lying around as I do, you likely already have all the requisite components to make a great time-lapse video. The following is a breakdown of my own experiment in time-lapse photography, which you can replicate or modify to suit your own needs.

Tags:

data journalism

,

drone journalism

,

photography

,

time lapse

,

time lapse photography

,

time-lapse

Monday, December 31, 2012

Canadian International Council and a year-end status report

Earlier this month, the Canadian International Council wrapped up its "Drone Week," which pooled the writings from national policy and technology experts, to help understand how drones could change the air and ground in three different contexts: Kill, Watch, Aid.

Much of this conversation revolved around the proliferation of drones as weapons. As I wrote in my own CIC piece for Opencanada.org, "Drones for Good," given the history of media's relationship with technology, this was only to be expected:

If we’re being dictionary-accurate, though, “drone” merely means an airplane or boat guided remotely. The first drone was invented by Nikola Tesla, who wowed audiences in New York City’s Madison Square Garden with a radio-controlled boat in 1898. His audience, baffled and scared by the demonstration, likely had little or no previous exposure to radio technology. It would be nearly a decade until the first public radio broadcast, a live transmission from the Metropolitan Opera House.Combine the public perception of drones with the public perception of the media and journalists, and it's easy to see how drone journalism faces and uphill battle. But, I wrote, limiting domestic drone use would have consequences.

A New York Times reporter asked the question that would dog the technology from that day on: What of the military applications for the tiny electric boat? “You do not see there a wireless torpedo,” Tesla replied, offended by the reporter’s suggestion. “You see there the first of a race of robots, mechanical men who will do the laborious work of the human race."

In other news, weather has been particularly miserable for flying drones as of late here in central Illinois.

The cold really isn't the limiting factor here, either. Cold temperatures make it difficult for small gas motors to operate (they rely on glow plugs to ignite the compressed mixture of air and fuel, which requires heat). But lithium polymer batteries are actually fairly resilient to the cold.

The autopilot might be the limiting factor in cold weather, as I'm finding out the ceramic resonator that keeps the autopilot microcontroller in sync can be thrown off by extreme temperatures. However, it's much easier to warm something up than cool something off from an electrical standpoint. Cold isn't fun, but it's not ultimately a deal-breaker.

Wind actually is the biggest problem. It's hard to fly my current fleet of drones in 15mph winds. It's not impossible to fly a drone in that kind of wind, it just requires a bigger drone (an 8 foot wingspan would be nice).

While I'm waiting for the weather to improve, I'm focusing on using drone equipment for other data-gathering applications, and working on drones that I can actually fly indoors. More on that in 2013.

Tags:

Canadian International Council

,

CIC

,

drone journalism

,

Opencanada.org

,

weather

Monday, November 26, 2012

An introduction to small drones - from the AMA

Go back just one or two years in the world of drones, and you'll notice a distinct separation between the price of these small, remotely-guided aircraft. At the top end, you had systems like the Gatewing X100 and the DraganFly X6 which cost $20,000 and up, with some models . These units were generally designed for commercial or government use, and with adequate training, can be flown "out of the box."

But for hobbyists and members of the DIY/Maker movement, similar products could be hacked together from GPS and gyro-equipped microcontrollers, RC electric motors, and RC radio equipment for about $1,000.

This price point has made drones very attractive to "hacktivists," or activists with a great deal of technical ability who use that expertise to further the goals of a political cause. Think Tim Pool and the Occucopter, anti-ACTA protestors in Estonia, N8 protestors in Argentina, or SHARK and its Angel Drone (recently shot down for the fourth time).

The video obtained from these aerial platforms have proved useful in rallying support and attention to political movements. Journalists would do well to take notes from how the hacktivists have deployed drones around the world -- because these methods can be easily transplanted into journalism.

The cost of drones has dropped considerably in recent years, now opening up a nice $2,000 - $15,000 range of drones that don't require much hacking experience at all. But there's just one big problem: regulations. There's currently not a place in the FAA regulations for a viable commercial pursuit of drones, and that includes commercial journalism.

There is, however, a place for government and research institutions to use drones. That place is called a Certificate of Authorization, or COA (pronounced "Koh-ah" in the industry).

But let's say you're not a government institution, and still want to fly a drone. There is still a place for you to fly a drone, albeit as a hobbyist.

The FAA regulation AC 91-57 allows anyone to fly a remote-controlled vehicle, for recreation, so long as the aircraft is not flown above 400 feet AGL (above ground level), or within 3 miles of an airport. You must also give way to full scale airplanes, should they enter your airspace (but that really shouldn't happen, given that the lowest legal limit for an airplane to fly is 500' AGL).

Since you're flying as a hobbyist, you should get to know the Academy of Model Aeronautics. The AMA dates back to 1936, and it's the largest association of its kind in America. Club members have years of experience dealing with nearly the exact same kind of controls, radio equipment and motors that make the majority of the $15,000-and-under drones work.

And as a paid member, you get $2.5 million in liability coverage, should your drone have an unfortunate series of events. Keep in mind that coverage is only valid if you follow AMA guidelines.

The latest issue of Model Aviation, which is AMA's official magazine, has quite a few pages devoted to drones. Apparently quadrotors are the biggest growth area for the entire RC hobby. Hobbyists are especially captivated by the aerial video capability of these drones (seeing a theme here?).

The December issue has a great write-up that's a good introduction into multi-rotor drones meant for hobbyists, but it's great for journalists as well.

An excerpt from the article:

But for hobbyists and members of the DIY/Maker movement, similar products could be hacked together from GPS and gyro-equipped microcontrollers, RC electric motors, and RC radio equipment for about $1,000.

This price point has made drones very attractive to "hacktivists," or activists with a great deal of technical ability who use that expertise to further the goals of a political cause. Think Tim Pool and the Occucopter, anti-ACTA protestors in Estonia, N8 protestors in Argentina, or SHARK and its Angel Drone (recently shot down for the fourth time).

The video obtained from these aerial platforms have proved useful in rallying support and attention to political movements. Journalists would do well to take notes from how the hacktivists have deployed drones around the world -- because these methods can be easily transplanted into journalism.

The cost of drones has dropped considerably in recent years, now opening up a nice $2,000 - $15,000 range of drones that don't require much hacking experience at all. But there's just one big problem: regulations. There's currently not a place in the FAA regulations for a viable commercial pursuit of drones, and that includes commercial journalism.

There is, however, a place for government and research institutions to use drones. That place is called a Certificate of Authorization, or COA (pronounced "Koh-ah" in the industry).

But let's say you're not a government institution, and still want to fly a drone. There is still a place for you to fly a drone, albeit as a hobbyist.

The FAA regulation AC 91-57 allows anyone to fly a remote-controlled vehicle, for recreation, so long as the aircraft is not flown above 400 feet AGL (above ground level), or within 3 miles of an airport. You must also give way to full scale airplanes, should they enter your airspace (but that really shouldn't happen, given that the lowest legal limit for an airplane to fly is 500' AGL).

Since you're flying as a hobbyist, you should get to know the Academy of Model Aeronautics. The AMA dates back to 1936, and it's the largest association of its kind in America. Club members have years of experience dealing with nearly the exact same kind of controls, radio equipment and motors that make the majority of the $15,000-and-under drones work.

And as a paid member, you get $2.5 million in liability coverage, should your drone have an unfortunate series of events. Keep in mind that coverage is only valid if you follow AMA guidelines.

The latest issue of Model Aviation, which is AMA's official magazine, has quite a few pages devoted to drones. Apparently quadrotors are the biggest growth area for the entire RC hobby. Hobbyists are especially captivated by the aerial video capability of these drones (seeing a theme here?).

The December issue has a great write-up that's a good introduction into multi-rotor drones meant for hobbyists, but it's great for journalists as well.

An excerpt from the article:

Multicopters come in all shapes and sizes. Although there are configuration differences, they all have the same basic components: pilot command and control, motors, propellers, ESCs, a frame, and a flight control module.The article also includes some interesting historical background on the origin of multicopters and similar aircraft. Read "Rise of the multicopter" here.

Depending on how advanced you want to be, multicopters may also have video cameras, GPS, compasses, barometers, sonar sensors, and telemetry. Often, many of the sensors and secondary options are built into the flight controller, which also houses the electronic gyros and accelerometers found on most multicopters.

Tags:

AMA

,

drone hacktivism

,

drone hobby

,

drone journalism

,

hacktivism

,

sUAS

Saturday, November 10, 2012

Activists record 8N protest with drones, continue to take lead on drone coverage

Progress in covering large events with aerial drones, especially protests, has been led almost exclusively by political activists. The most recent effort by activists to use drones document the scale of anti-government demonstrations comes from Argentina, where the “8N” demonstration on Thursday, November 8.

That day, some 30,000 Argentinians protested economic conditions, government corruption and the fear that President Cristina Fernandez will attempt to end her term limit.

According to the group El Cipayo Argentino, the government had closed down the airspace ahead of the protest, and did not allow news helicopters to cover the event. So the group came up with a low-budget workaround: they built their own aerial drone to provide coverage from the sky.

As you can hear from the video, the camera attached to the drone picked up a great deal of propeller and motor noise. The fact that protestors can be heard above the din of the whirring motors speaks volumes.

Al Jazeera has a write up about the protest and the activists behind the drone here.

Friday, November 9, 2012

We need more drones because we’re having more big disasters.

The images of an inundated New York City certainly were eye-catching. But it isn’t until you start parsing the data that you start to really understand how bad things got for the East Coast.

Some of the most startling stats: winds pegged at 90 miles an hour when Sandy made landfall as a tropical storm. It left 185 dead between Jamaica and its terminus in the US. It was the second costliest hurricane in recorded history after Katrina, with $52.4 billion in damages. Five thousand commercial airline flights cancelled. Across 26 states, up to 80 million were affected. Eight and a half million people without power after the storm.

Even 11 days after the storm, with freezing winter temperatures closing in, 428,000 in New York and New Jersey remain without power.

Aon Benfield, an insurance broker that specializes in catastrophe management, crunched the numbers and found something just as remarkable about hurricane/tropical storm Sandy. Well, perhaps not so much about the storm itself, but how it fits into recent weather events and climate change in general.

“Devastating Hurricane Sandy was the eleventh billion-dollar weather-related disaster in the U.S. so far this year, and the most expensive,” wrote Wunderground.com’s Jeff Masters, of Aon Benfield’s latest report. “This puts 2012 in second place for most U.S. billion-dollar weather disasters behind 2011, when NOAA's National Climatic Data Center (NCDC) counted fourteen such disasters.”

Meanwhile, climate scientists noted that not only did global warming make such a historic slew of storms possible, it also made the sea level rise, thus increasing the damage to coastal areas.

“Sandy threw the ocean at the land, and because of global warming, there were about eight inches more ocean to throw,” wrote Chris Mooney on The Climate Desk. “As the water level increases, the level of damage tends to rise much more steeply than the mere level of water itself.”

When Thailand was flooded in 2011, the government contracted a drone to scout out where flooding had occurred, which helped make decisions about where and when to release flood gates. The contractor flew more than 60 flights over a period of 45 days, and claimed that the data obtained from those flights helped prevent the city of Bangkok from suffering more during that catastrophe.

That same year, back in the states, freelance journalist and storm chaser Aaron Brodie took sweeping shots of the Jersey Shore with his own multicopter before and after Hurricane Irene. He uploaded this footage on YouTube, but amended his post after Sandy:

“Irene was child's play in comparison to Superstorm Sandy. In fact, there was no real damage from Irene,” Brodie wrote.

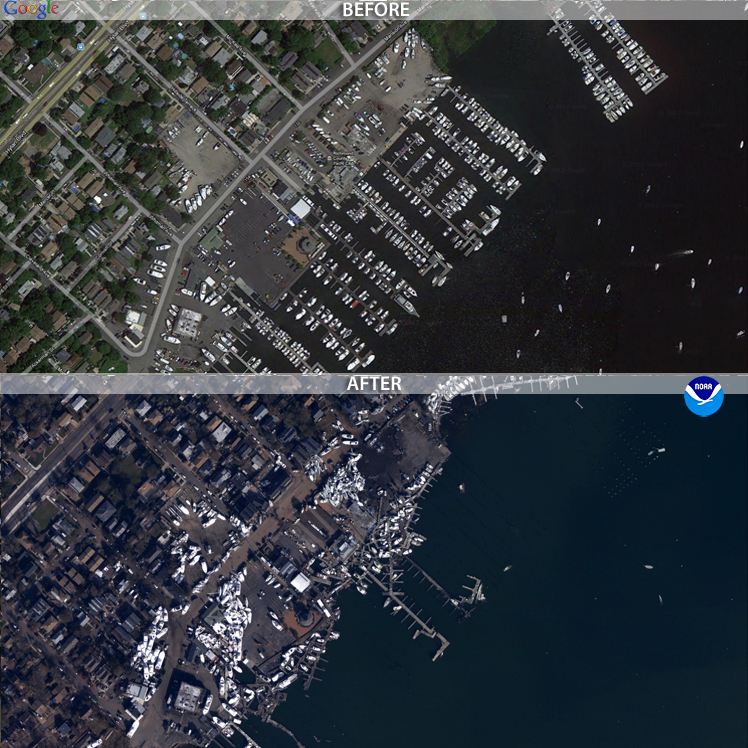

The public wasn’t able to obtain coverage from drones for Sandy. Some news sites did, however, post before and after photos of New York and New Jersey. These post-sandy aerial photos were obtained by the National Geodetic Survey, with the help of NOAA’s King Air and Twin Otter remote-sensing aircraft. The photos were set side-by-side with historic satellite imagery, allowing users to drag these images to do their own comparisons.

Because of the prohibitive cost of aerial photomapping, these images were gathered by government agencies. But, if FAA regulations allowed it, the job could have easily been done with a $1,000 aerial drone. That puts it within reach of even independent and backpack journalists. Or concerned members of the community.

If the climate models hold true, there’s going to be more “superstorms” like Sandy every year. There will be more billion-dollar disasters, more lives lost, more power outages, and the public will need more information about how those disasters are affecting their communities.

Drones are especially capable of giving quick data on the scope, or extent, of large-scale disasters. Now is the time for journalists to learn and perfect tools like the drone to give the public that information.

Photo at the top of the post is of post-Sandy flooding in Haiti, via the Flikr photostream of United Nations Stabilization Mission In Haiti.

Tags:

disaster reporting

,

drone

,

drone journalism

,

dronejournalism.org

,

drones

,

Hurricane Sandy

,

natural disasters

,

Sandy

,

sUAS

,

UAS

,

UAV

Thursday, October 11, 2012

The case of Chicken v Bomber, and how it might impact drone law

The first thing you should know is if you run afoul (pun very much intended) of the law, I can’t bail you out. If you read the “About the Author” page on MentalMunition.com, you’ll note that I’m not a lawyer. My only legal qualifications are an undergraduate course in media law.

Having said that, I started researching drone law and writing back in March, shortly before the Brookings Institution organized a panel on domestic drones and privacy. The ACLU had just published a report in December 2011 called “Protecting Privacy from Aerial Surveillance: Recommendations for Government Use of Drone Aircraft” that referenced important Supreme Court cases that might play a role in drone law.

Just this week, Alexis Madrigal, the senior editor for the Technology channel at the Atlantic, wrote about two cases that could have some bearing on drone law, Guille v. Swan, and U.S. v. Causby. The latter involved dead chickens.

I’ll be writing about that case here. When we talk about drone laws, we’re talking about a speculative thing. To date, no journalist has been sued for violating rights of privacy with an unmanned aerial system. There is no legal precedent specifically for drones as of yet, although that might change in the near future. As drone technology proliferates, so too does the potential for abuse and for court cases.

But the United States courts are not absent of precedent that would come up in a privacy case involving drones. It’s is important to keep in mind that in many cases drone journalism is a form of aerial photography, albeit an unmanned form of aerial photography. Additionally, cases that consider whether the National Airspace System (NAS) is public or private are highly relevant.

Tags:

Alexis Madrigal

,

Atlantic

,

drone journalism

,

drone law

,

drones

,

privacy

,

U.S. v Causby

Wednesday, October 3, 2012

Journalism Drone Development: aerial photo mosiacs, and what's the spatial resolution on this drone, anyway?

Above is an aerial mosaic -- a series of 11 photos taken from a small unmanned aerial vehicle (colloquially known as a drone) that have been stitched together in a mosaiking program.

That program, Microsoft Image Composite Editor, is normally used to stitch together a series of sweeping photos taken from the ground to make a single panoramic image. However, the algorithm used to find and match the edges of a series of sweeping photos of, say, the Grand Canyon, is the same algorithm needed to fit photos together to make a map or similar map-esque image from aerial photos.

So, what kind of drone journalism could you do with this kind of image? Aerial photographers have been able to capture a breathtaking, panoramic view of Moscow protests from drones. These drones offer a perspective that is especially helpful at documenting the scope or extent of protests, political rallies, construction projects, landmarks, geographic features, and natural and man-made disasters.

But what kind of data journalism can you do with these drones? That's to say, what kind of hard data can you obtain from these images to launch investigations? How about proving the existence of or extent of something, such as oil spills, wild fires, droughts, or lax construction codes following a disaster, with actual metrics?

Subscribe to:

Posts

(

Atom

)