Showing posts with label dronejournalism.org. Show all posts

Showing posts with label dronejournalism.org. Show all posts

Monday, March 4, 2013

A map of all the drone laws in the United States.

The ACLU recently published on its technology blog a list of 28 states that are pursuing regulations for unmanned aircraft systems, or UAS. They're more commonly referred to as "drones," and in fact many of the proposed laws use that exact word.

I dug further to find out what lawmakers are actually proposing. You may click on individual states in the above map to learn more about specific legislation.

Out of the 28 states, 14 are proposing limitations only to law enforcement. In most cases, proposed legislation would make it illegal for law enforcement to use an unmanned aircraft without a warrant.

Some also call for evidence obtained from a "drone" to be destroyed after a specified period. A few ban any government entities from using the technology altogether.

Friday, November 9, 2012

We need more drones because we’re having more big disasters.

The images of an inundated New York City certainly were eye-catching. But it isn’t until you start parsing the data that you start to really understand how bad things got for the East Coast.

Some of the most startling stats: winds pegged at 90 miles an hour when Sandy made landfall as a tropical storm. It left 185 dead between Jamaica and its terminus in the US. It was the second costliest hurricane in recorded history after Katrina, with $52.4 billion in damages. Five thousand commercial airline flights cancelled. Across 26 states, up to 80 million were affected. Eight and a half million people without power after the storm.

Even 11 days after the storm, with freezing winter temperatures closing in, 428,000 in New York and New Jersey remain without power.

Aon Benfield, an insurance broker that specializes in catastrophe management, crunched the numbers and found something just as remarkable about hurricane/tropical storm Sandy. Well, perhaps not so much about the storm itself, but how it fits into recent weather events and climate change in general.

“Devastating Hurricane Sandy was the eleventh billion-dollar weather-related disaster in the U.S. so far this year, and the most expensive,” wrote Wunderground.com’s Jeff Masters, of Aon Benfield’s latest report. “This puts 2012 in second place for most U.S. billion-dollar weather disasters behind 2011, when NOAA's National Climatic Data Center (NCDC) counted fourteen such disasters.”

Meanwhile, climate scientists noted that not only did global warming make such a historic slew of storms possible, it also made the sea level rise, thus increasing the damage to coastal areas.

“Sandy threw the ocean at the land, and because of global warming, there were about eight inches more ocean to throw,” wrote Chris Mooney on The Climate Desk. “As the water level increases, the level of damage tends to rise much more steeply than the mere level of water itself.”

When Thailand was flooded in 2011, the government contracted a drone to scout out where flooding had occurred, which helped make decisions about where and when to release flood gates. The contractor flew more than 60 flights over a period of 45 days, and claimed that the data obtained from those flights helped prevent the city of Bangkok from suffering more during that catastrophe.

That same year, back in the states, freelance journalist and storm chaser Aaron Brodie took sweeping shots of the Jersey Shore with his own multicopter before and after Hurricane Irene. He uploaded this footage on YouTube, but amended his post after Sandy:

“Irene was child's play in comparison to Superstorm Sandy. In fact, there was no real damage from Irene,” Brodie wrote.

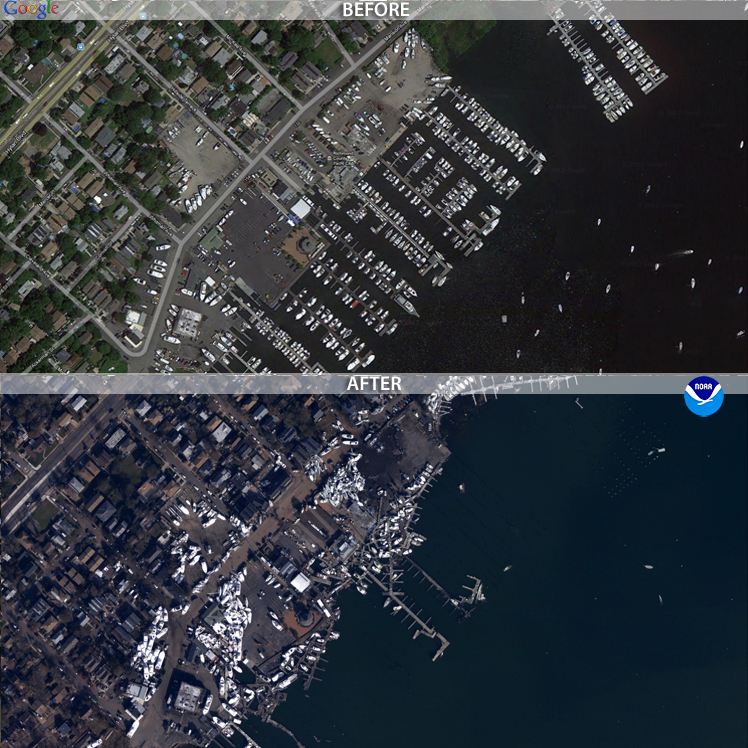

The public wasn’t able to obtain coverage from drones for Sandy. Some news sites did, however, post before and after photos of New York and New Jersey. These post-sandy aerial photos were obtained by the National Geodetic Survey, with the help of NOAA’s King Air and Twin Otter remote-sensing aircraft. The photos were set side-by-side with historic satellite imagery, allowing users to drag these images to do their own comparisons.

Because of the prohibitive cost of aerial photomapping, these images were gathered by government agencies. But, if FAA regulations allowed it, the job could have easily been done with a $1,000 aerial drone. That puts it within reach of even independent and backpack journalists. Or concerned members of the community.

If the climate models hold true, there’s going to be more “superstorms” like Sandy every year. There will be more billion-dollar disasters, more lives lost, more power outages, and the public will need more information about how those disasters are affecting their communities.

Drones are especially capable of giving quick data on the scope, or extent, of large-scale disasters. Now is the time for journalists to learn and perfect tools like the drone to give the public that information.

Photo at the top of the post is of post-Sandy flooding in Haiti, via the Flikr photostream of United Nations Stabilization Mission In Haiti.

Tags:

disaster reporting

,

drone

,

drone journalism

,

dronejournalism.org

,

drones

,

Hurricane Sandy

,

natural disasters

,

Sandy

,

sUAS

,

UAS

,

UAV

Monday, September 10, 2012

Muck Rack hosts Drone Journalism Q&A

What are the rules on drone use right now? What would you use one for in journalism? What about ethics? Last week, the Muck Rack

invited Nebraska Drone Journalism Lab's Matt Waite and

DroneJournalism.org's Matthew Schroyer to a Twitter Q&A on drones to

help answer those questions and more.

Read more on Muck Rack's site, which documented the fourteenth installment of their #muckedup chat.

Reposted from DroneJournalism.org

Read more on Muck Rack's site, which documented the fourteenth installment of their #muckedup chat.

Reposted from DroneJournalism.org

Tags:

#muckedup

,

drone journalism

,

dronejournalism.org

,

Matt Schroyer

,

Matt Waite

,

Muck Rack

,

Nebraska Drone Journalism Lab

,

QA

,

Twitter

Thursday, August 9, 2012

Drone Journalism: News that Flies

The idea of using homebrew drones for independent journalism is picking up steam globally.

I just got a digital copy of a story from Aug-Sept issue of seLecT, the Brazilian art & design magazine, which features a story about that same topic. In it, writer and art professor Nina Gazire interviews the Occucopter developer Tim Pool, Nebraska Drone Journalism Lab professor Matt Waite, and myself.

As one would expect, the story is in Portuguese, so here it is translated (via Google):

AT THE END OF 2011, A JOURNALIST OF 25 YEARS HAS BECOME THE SPOKESMAN OF ONE OF THE MORE RECENT EVENTS DISSATISFACTION WITH THE WORLD ECONOMIC CRISIS.

Tags:

drone journalism

,

Drone Journalism Lab

,

dronejournalism.org

,

drones

,

independent journalism

,

Matt Waite

,

Nina Gaizre

,

Occucopter

,

sUAS

,

Tim Pool

,

UAS

Monday, June 4, 2012

After months of development and heartache, the journalism drone takes flight

Months of planning, training, re-design, and fabrication finally paid off for DroneJournalism.org developers, as we successfully launched a journalism drone for the first time on Sunday, June 3, in the small Illinois town of Tuscola.

Eventually the drone will be equipped with an Arduino-based autopilot (APM 2.0) and cameras to collect aerial photography and aerial photomaps for use in journalism investigations. JournoDrone 2 is the successor to JournoDrone One, which was meant to be a "Unmanned Aerial System (sUAS) for journalists that is powerful, durable, transportable, affordable, upgradeable and supported by a community of experts."

JournoDrone One was smashed to pieces during testing in two months ago. Since then, I had been applying the lessons learned from the first drone to make a drone for journalism that was stronger and more capable.

The June 3 flight was a basic shakedown of the airframe, without autopilot or sensors, to prove the airworthiness of the drone. While the airframe proved slightly heavy and unpredictable at times, our indication is with some modification it will be a competent flyer for our purposes.

JournoDrone 2 is based on the "FPV Raptor" radio controlled airplane with some important modifications, the most important of which is carbon fiber-reinforced fuselage. The airplane had a fairly good track record as a First Person Video drone, so we didn't feel that we needed to change the layout of the craft. Yet we needed to have an extra layer of security to make it more of a "tool" rather than "toy."

While we had some initial concerns about weight gain, the two layers of carbon fiber and epoxy proved its worth when the aircraft experienced a sudden gust of wind in its second flight and crashed. While the impact separated the motor pod, chipped the propeller, bent the motor shaft, and cracked the casing of an on-board camera, the fuselage was totally unscathed. We were not able to recover the on-board video of that second flight.

Monday, May 14, 2012

Flight of the JournoBalloon: An intro to balloon photography. Also, I lose the first JournoBalloon.

We almost had it. After months of research, development and heartache, DroneJournalism.org was about to have its very first aerial photographs. And while it wasn't going to be from a drone, these photos would be gathered easily and available instantly.

The balloon went up, the line went out, but something didn't seem right. And then... well, in short, on Wednesday, May 2, at approximately 4:00 p.m., we almost had it. What was it, exactly?

Wednesday, May 2, 2012

Partnerships unlock the real potential of drones, especially in drone journalism.

Yesterday, Salon ran a piece on the proliferation of drones at research universities. As Jefferson Morley wrote, universities are at the are at the forefront of developing the unmanned aerial systems that will be monitoring crops, assessing damage, and doing a number of other tasks at home.

That may not come as much of a surprise to anyone who's been following drones in the past couple of weeks. Recently, Electronic Frontier Foundation published the list of public institutions and government agencies who had current or expired authorization to fly drones.

Some applicants were obscure. Herrington, Kansas -- a town of 2,526 souls -- applied for authorization to fly drones. But 25 of the 62 agencies were institutes of higher learning, and many were surprised at how few agencies had applied for authorization.

However, there's a buried lede in this story: universities aren't just developing drones, they're developing these drones in partnerships with other entities. This isn't happening in an ivory-tower vacuum.

That may not come as much of a surprise to anyone who's been following drones in the past couple of weeks. Recently, Electronic Frontier Foundation published the list of public institutions and government agencies who had current or expired authorization to fly drones.

Some applicants were obscure. Herrington, Kansas -- a town of 2,526 souls -- applied for authorization to fly drones. But 25 of the 62 agencies were institutes of higher learning, and many were surprised at how few agencies had applied for authorization.

However, there's a buried lede in this story: universities aren't just developing drones, they're developing these drones in partnerships with other entities. This isn't happening in an ivory-tower vacuum.

Monday, April 23, 2012

Drone Journalism Development: Final Lessons from JournoDrone One

When JournoDrone One met its end last month, taking one final dive into the grass and shattering into foamy bits, it dashed the hopes of DroneJournalism.org developers of an easy solution to drone journalism. However, we were well aware that this enterprise had a learning curve. And we did have some measure of success, and learned some valuable lessons that will help us and other drone journalists in the future.

We can say for certain that the drone flew. It didn’t fly very high – 12 feet or so – or for very long – perhaps 5 seconds at most. But it did fly.

Above is the only on-board footage of the first and only flight of JournoDrone One. For most of the video, the shadow of the drone’s nose is visible in the bottom of the image, except for the last few seconds when the drone lifts off. That’s when the image starts to bob and weave, because there’s no longer wheels and landing gear keeping the craft stable.

Only one minute and eight seconds could be recovered from the GoPro HD camera mounted to the bottom of the craft. That’s because I maneuvered the aircraft with very little altitude, and inadvertently sent it in a downward trajectory. Upon impact, the GoPro separated from its mounting case and ejected its SD card before it had a chance to write the remainder of the flight to the card. This also corrupted the file, and so a freeware program was used to recover what little footage the GoPro managed to record.

What went into the drone, and what did I get out of it? Here’s the details.

Friday, April 13, 2012

Drone Journalism - Cheap Coverage from the Sky for TV News Stations

Although we’re several years away in terms of regulation and technology for making drones a feasible, low-cost platform for television news, the television news industry has started to talk about using drones to enhance coverage.

Myself, along with Matt Waite of Nebraska’s Drone Journalism lab, were recently interviewed by the television news trade journal TV Technology. It briefly mentions DroneJournalism.org and our (unfortunately now departed) JournoDrone One (pictured above).

Tom Butts, the writer of the piece and the editor in chief of the TV Technology magazine, focuses mainly on drones as a cheap alternative to manned helicopters for live news events. He also draws attention to how ethical or technical mishaps with drone technology could slow or prevent the adoption of drone technology in the TV broadcasting industry.

Here’s some excerpts below:

Drone Journalism: The News Choppers of Tomorrow…

By Tom Butts

For TV news crews, operating an “eye in the sky” means hundreds of thousands of dollars per year in aircraft maintenance and fuel costs. Using choppers also comes with inherent risks that have resulted in numerous accidents over the years.

As stations look to save money while reducing safety concerns, some in the news business are beginning to examine the use of unmanned aerial vehicles to obtain highly valuable news coverage from above. While it’s a relatively new concept for journalists, the technology of “drone journalism” is familiar and extremely cost-effective when compared to traditional aircraft.

In essence, drone journalism involves the use of remote-controlled small aircraft outfitted with cameras to acquire footage from the air. What defines “aircraft” could be anything from a toy helicopter purchased at the local mall to more sophisticated devices, and the camera could be a typical point-and-shoot to a more expensive DSLR with video capabilities.

There’s just one problem. The use of such devices is illegal in the United States – for now, at least. Last month, as part of its latest budget, Congress gave the Federal Aviation Administration until 2015 to develop a set of rules and guidelines authorizing the commercial use of such remote-controlled unmanned aerial devices. And several researchers and entrepreneurs are exploring the technical – and perhaps even more important – ethical uses of these drones.

JOURNODRONE

Matthew Schroyer, a drone and data journalist at the University of Illinois-Champagne [sic] created dronejournalism.org as a forum to discuss and share ideas about the subject and is developing a UAV dubbed the “JournoDrone,” based on designs from diydrones.com. Schroyer is approaching the subject matter more from a data-gathering standpoint, using still photographs to stitch together maps from aerial surveying.

“We are getting to the point where a journalist can build a drone for himself and fly it and use it to collect all sorts of interesting data and information that you couldn’t get before without this perspective,” Schroyer said. “These platforms are so versatile… I could really see this technology taking off and being adopted in a lot of newsrooms.”

Up until now, must of the public has become aware of drones through news reports about their use in military operations – and then only when something goes wrong. This has created a public relations problem that both [Matt] Waite [a professor of journalism at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln] and Schroyer believe could be compounded if the commercial use of drones is abused, specifically to violate people’s privacy.

“We don’t send photographers to people’s houses with long telephoto lenses and we don’t trespass on someone’s private property to use those lenses to take pictures through people’s windows,” Waite said. “Why would using a drone make that any more OK? It wouldn’t. There are significant questions of people’s rights, the right to assembly and the government’s powers to monitor people that come with this technology.”

…

What happens if the paparazzi start using drone cameras to spy on celebrities? How far would they go? This is one of Schroyer’s main concerns. “The entire field of dorne journalism could be stifled by one incident and then we could lose all this reporting ability,” he said. “We don’t want that to happen.”

You can read the full story at http://www.nxtbook.com/nxtbooks/newbay/tvt_20120411/index.php#/70

Meantime, I'll be delivering news on the status of JournoDrone One here and on DroneJournalism.org in the near future. That update will have information on our progress, where we're headed in the near future, as well as advice for drone journalists who are trying to develop their own drones.

Friday, March 2, 2012

The Harrisburg tornado, the JournoDrone, and a well-deserved crash

|

| Aerial photograph of Harrisburg, IL. Not taken by JournoDrone One. |

Today, the southern Illinois town of Harrisburg is morning six of its own who were killed by a 170 mile per hour, 200 yard tornado. It was one of the 16 tornadoes that ripped through Nebraska, Kansas, Missouri, Illinois and Kentucky, claiming 13 lives.

Tuesday night, while news networks came from far and wide to cover the devastation on the ground, I worked to prepare JournoDrone One to film the disaster from the sky. For better or worse, the drone never made it to Harrisburg.

JournoDone One is a test mule for DroneJournalism.org, which myself and fellow drone journalism developer Acton Gorton hope will pave the way for a low-cost, highly durable and transportable small Unmanned Aerial System (sUAS) for journalists.

JD-01 had never flown a mission before, let alone been tested. So the idea of rushing to Harrisburg and filming anything was a long shot, but something I felt I needed to try. This was a disaster just three and a half hours’ drive from home base, and if I had anything to say about it, I would be putting my equipment to good use. And I do venture to natural disasters on a whim.

Of course, it wouldn’t do any good to drive to the storm-ravaged town of Harrisburg just to nose-dive a drone into the rubble after takeoff. The town had enough grief and did not need some clumsy pilot crashing drones into things and making things worse. So instead, I had a test flight in Champaign, where I dove the drone into a freezing field. Here’s what happened.

Tags:

aerial photography

,

drone

,

drone crash

,

drone journalism

,

dronejournalism.org

,

GoPro

,

GoPro Hero2

,

Harrisburg

,

JournoDrone One

,

southern Illinois

,

sUAS

,

tornadoes

Saturday, February 25, 2012

A word about regulation, applications of drone journalism

This week, I had the pleasure of talking about drones and drone journalism with Drone Journalism Lab founder Matt Waite, and the Joseph Paiva, the Chief Operating Officer of drone developer Gatewing, on Washington DC's "The Kojo Nnamdi Show." A lot of ground was covered in that hour-long show, but I wanted to re-cap and expand on a few of the things I said during the show.

- REGULATIONS

For some time, there has been and continues to be frustration in the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) rules on small Unmanned Aerial Systems (sUAS). To review the terminology, we refer to a "drone" as the object that is flying in the air. A UAS implies there is more to this than simply the drone; it's a system of technology with a ground-based operator. On the show, I presented the question about FAA UAS regulation, and that was "what is recreational?":

"I mean, that's one of the rules that says that you can fly under 400 feet away from built-up areas, away from airports, but it's not so clear as what recreation really is. Is that what a nonprofit is when they're trying to collect drone journalism? Is that what a organization who is trying to advocate for animals -- Is that what they're doing when they're flying a drone over a pigeon shoot in South Carolina? And so it is kind of debatable, and it's not really codified into any regulation at this point. "

I'll explain. The FAA regulations as they are today provide a space for recreational drones to operate without special certification, and requires special certification for civilian commercial drones. Those UAS must operate under 400 feet and away from built-up areas and airports.

But where do nonprofit, advocacy, and education lie on that recreational-commercial spectrum? Nowhere does the FAA provide a deffinition for recreation. Some university researchers have been told they need a COA (Certificate of Authorization) to operate their experimental drones for educational purposes, which often times take months to process. Additionally, the FAA will not grant any certificate to anyone operating a drone for profit.

After the show, I received a call from a reporter for a broadcast industry magazine, and I told him that it had been five years since the FAA regulations, and I didn't expect any regulations until the 2015 deadline. He sounded shocked, and asked for clarification.

Five years ago, on February 13, 2007, FAA issued a decree, or "Notice of Policy," in the (Docket No. FAA–2006–25714; Notice No. 07–01) which essentially shut down all civil operation of drones (other than recreational/model activity) in the United States.

That Notice of Policy for Unmanned Aircraft Systems said that in order to pilot a drone for anything but a recreational purpose, you need to obtain an airworthiness certificate in an experimental category for your UAS. This certification just the same as any other experimental aircraft, and is required regardless if you were going to fly your UAS under the exact same restrictions as recreational UAS: fly under 400 feet and away from "built-up areas." Even with this certification, you cannot fly the drone for commercial purposes (which would include commercial media).

More than a year later on April 10, 2008, the FAA issued another decree. This established a small UAS Aviation Rulemaking Committee (ARC) to "conduct a formal safety analysis of small UAS, and then promulgate federal regulations for their design, operation and registration." What came out of that ARC? I don't know.

Patrick Egan, from Remote Control Aerial Photography Association (RCAPA), was on that committee and said there was a "lack of comprehensive action." According to RCAPA president Rick Connolly, who Egan interviewed for sUASnews.com, "Even the members that were part of the process feel nothing came of it and all their hard work was put in the circular file."

Then, in June, a new ARC (ARC 2.0) was created. sUAS News had to file a FOIA request to find out who was on the rulemaking committee and what its charter was. This time around, the ARC seems to be dominated by those. Of the 22 committee members who are not from the FAA, 11 are defense contractors, and there is only one who potentially represents the non-defense commercial drone industry. This has generated a level of skepticism and criticism from RCAPA and other commercial and recreational drone groups.

Some news reports said that proposed rules would come out of ARC 2.0 by December 2011. That never happened.

More than a year ago, the FAA grounded the multicopters of the media company MI6 Films, and told the news website The Daily that it could not longer use drones for its reporting. Meanwhile, ABC, the Australian Broadcasting Corporation, is now flying its own news drone, and MI6 has since found work in other countries. Australia had rules governing UAVs on the books since 2002. The inability to create a space for commercial drones is hampering not just journalism, but innovation that could spark economic growth in a time of economic stagnation.

As I said on the radio show, the FAA has a tremendous burden on its shoulders. It has to make the national airspace safe, and it has to protect people on the ground from harm. That responsibility should not be taken lightly. However, that does not make the delays any less frustrating. And it does not make any less confusing the fact that you need special certification for a craft used for commercial or educational purposes, while the exact same craft can be operated for recreational purposes without any authorization whatsoever from the FAA. Inconsistency in regulations provide ample opportunity to misinterpret the rules.

- APPLICATIONS

I mentioned on the show that a fixed-wing drone could potentially stay aloft for thirty minutes, up to four hours, and beyond. While it's true that a fixed-wing craft can stay aloft for longer periods than a multicopter, the multicopter is better at fulfilling other roles.

Multicopters are uniquely gifted with the ability to hover in a fixed position for the entire duration of its flight. They are also better at negotiating obstacles and maneuvering in tight spaces, as they do not require forward momentum to provide them with lift. Relative to their overall size, multicopters are also able to lift a heavier load than their fixed-wing counterparts. They really are the ideal platforms for many aerial photography and filming applications.

Balloons are another platform for aerial photography. They trump fixed-wing and multirotor craft for "loitering time," the amount of time the craft can stay above a desired target. Being a tethered aircraft, they are also less stringently regulated here in the United States, meaning currently you can use them legally in more circumstances than you would a multicopter or fixed-wing drone. They do have one shortfall, however, and that is they aren't nearly as mobile or controllable as their counterparts. They drift with the air current, and are only as mobile as the operator is able to re-locate the tether.

Dronejournalism.org is pursuing multicopters, but our most complete project at the moment is a fixed-wing drone. That's because the fixed-wing drone is perfect for being able to photomap swaths of land. And with the proper equipment, they can aim a camera in such a way that it lessens the negative effects of circling above a target. In other words, the camera can pan, tilt, and zoom so that the direction the drone is heading at the time is nearly arbitrary.

Recently, we started the motor on that drone for the first time. Weather has hampered our flying the drone for the time being. I'll leave you with video of that moment. It's filmed from the same camera (a GoPro2) that we'll be mounting to to the drone in the future.

- REGULATIONS

For some time, there has been and continues to be frustration in the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) rules on small Unmanned Aerial Systems (sUAS). To review the terminology, we refer to a "drone" as the object that is flying in the air. A UAS implies there is more to this than simply the drone; it's a system of technology with a ground-based operator. On the show, I presented the question about FAA UAS regulation, and that was "what is recreational?":

"I mean, that's one of the rules that says that you can fly under 400 feet away from built-up areas, away from airports, but it's not so clear as what recreation really is. Is that what a nonprofit is when they're trying to collect drone journalism? Is that what a organization who is trying to advocate for animals -- Is that what they're doing when they're flying a drone over a pigeon shoot in South Carolina? And so it is kind of debatable, and it's not really codified into any regulation at this point. "

I'll explain. The FAA regulations as they are today provide a space for recreational drones to operate without special certification, and requires special certification for civilian commercial drones. Those UAS must operate under 400 feet and away from built-up areas and airports.

But where do nonprofit, advocacy, and education lie on that recreational-commercial spectrum? Nowhere does the FAA provide a deffinition for recreation. Some university researchers have been told they need a COA (Certificate of Authorization) to operate their experimental drones for educational purposes, which often times take months to process. Additionally, the FAA will not grant any certificate to anyone operating a drone for profit.

After the show, I received a call from a reporter for a broadcast industry magazine, and I told him that it had been five years since the FAA regulations, and I didn't expect any regulations until the 2015 deadline. He sounded shocked, and asked for clarification.

Five years ago, on February 13, 2007, FAA issued a decree, or "Notice of Policy," in the (Docket No. FAA–2006–25714; Notice No. 07–01) which essentially shut down all civil operation of drones (other than recreational/model activity) in the United States.

That Notice of Policy for Unmanned Aircraft Systems said that in order to pilot a drone for anything but a recreational purpose, you need to obtain an airworthiness certificate in an experimental category for your UAS. This certification just the same as any other experimental aircraft, and is required regardless if you were going to fly your UAS under the exact same restrictions as recreational UAS: fly under 400 feet and away from "built-up areas." Even with this certification, you cannot fly the drone for commercial purposes (which would include commercial media).

More than a year later on April 10, 2008, the FAA issued another decree. This established a small UAS Aviation Rulemaking Committee (ARC) to "conduct a formal safety analysis of small UAS, and then promulgate federal regulations for their design, operation and registration." What came out of that ARC? I don't know.

Patrick Egan, from Remote Control Aerial Photography Association (RCAPA), was on that committee and said there was a "lack of comprehensive action." According to RCAPA president Rick Connolly, who Egan interviewed for sUASnews.com, "Even the members that were part of the process feel nothing came of it and all their hard work was put in the circular file."

Then, in June, a new ARC (ARC 2.0) was created. sUAS News had to file a FOIA request to find out who was on the rulemaking committee and what its charter was. This time around, the ARC seems to be dominated by those. Of the 22 committee members who are not from the FAA, 11 are defense contractors, and there is only one who potentially represents the non-defense commercial drone industry. This has generated a level of skepticism and criticism from RCAPA and other commercial and recreational drone groups.

Some news reports said that proposed rules would come out of ARC 2.0 by December 2011. That never happened.

More than a year ago, the FAA grounded the multicopters of the media company MI6 Films, and told the news website The Daily that it could not longer use drones for its reporting. Meanwhile, ABC, the Australian Broadcasting Corporation, is now flying its own news drone, and MI6 has since found work in other countries. Australia had rules governing UAVs on the books since 2002. The inability to create a space for commercial drones is hampering not just journalism, but innovation that could spark economic growth in a time of economic stagnation.

As I said on the radio show, the FAA has a tremendous burden on its shoulders. It has to make the national airspace safe, and it has to protect people on the ground from harm. That responsibility should not be taken lightly. However, that does not make the delays any less frustrating. And it does not make any less confusing the fact that you need special certification for a craft used for commercial or educational purposes, while the exact same craft can be operated for recreational purposes without any authorization whatsoever from the FAA. Inconsistency in regulations provide ample opportunity to misinterpret the rules.

- APPLICATIONS

I mentioned on the show that a fixed-wing drone could potentially stay aloft for thirty minutes, up to four hours, and beyond. While it's true that a fixed-wing craft can stay aloft for longer periods than a multicopter, the multicopter is better at fulfilling other roles.

Multicopters are uniquely gifted with the ability to hover in a fixed position for the entire duration of its flight. They are also better at negotiating obstacles and maneuvering in tight spaces, as they do not require forward momentum to provide them with lift. Relative to their overall size, multicopters are also able to lift a heavier load than their fixed-wing counterparts. They really are the ideal platforms for many aerial photography and filming applications.

Balloons are another platform for aerial photography. They trump fixed-wing and multirotor craft for "loitering time," the amount of time the craft can stay above a desired target. Being a tethered aircraft, they are also less stringently regulated here in the United States, meaning currently you can use them legally in more circumstances than you would a multicopter or fixed-wing drone. They do have one shortfall, however, and that is they aren't nearly as mobile or controllable as their counterparts. They drift with the air current, and are only as mobile as the operator is able to re-locate the tether.

Dronejournalism.org is pursuing multicopters, but our most complete project at the moment is a fixed-wing drone. That's because the fixed-wing drone is perfect for being able to photomap swaths of land. And with the proper equipment, they can aim a camera in such a way that it lessens the negative effects of circling above a target. In other words, the camera can pan, tilt, and zoom so that the direction the drone is heading at the time is nearly arbitrary.

Recently, we started the motor on that drone for the first time. Weather has hampered our flying the drone for the time being. I'll leave you with video of that moment. It's filmed from the same camera (a GoPro2) that we'll be mounting to to the drone in the future.

Tags:

ABC drone

,

drone journalism

,

drone regulations

,

dronejournalism.org

,

drones

,

FAA

,

Gatewing

,

Matt Waite

,

sUAS

,

The Kojo Nnamdi show

,

UAS regulations

Tuesday, February 21, 2012

Project JournoDrone: A fixed-wing drone system for journalism

From Dronejounrnalism.org:

Developers at DroneJournalism.org are launching a project to build a low-cost aerial photo platform for journalists, using a combination of off-the-shelf radio-control components and open source electronics. Their goal is to develop a small Unmanned Aerial System (sUAS) for journalists that is powerful, durable, transportable, affordable, upgradeable and supported by a community of experts.

Now one month into the project, development on “JournoDrone One,” or JD-1, is approximately 20 percent complete. DroneJournalism.org is working to secure funding to complete the project by the summer of 2012. The knowledge gained from making and using the drone for aerial photography will allow DroneJournalism.org to bring a similar system to journalists worldwide.

Leading the project is Matthew Schroyer, the founder of DroneJournalism.org, who holds a master’s in journalism from the University of Illinois. Mr. Schroyer has a background in engineering, experience with small, radio-control devices, and experience in using Geographic Information Systems (GIS) for data journalism purposes.

“We hope this is the first of many drones that DroneJournalism.org will develop,” he said. “It’s a practical exercise of existing off-the-shelf drone technology, and our first step into a frontier that could greatly expand public knowledge.”

Developers at DroneJournalism.org are launching a project to build a low-cost aerial photo platform for journalists, using a combination of off-the-shelf radio-control components and open source electronics. Their goal is to develop a small Unmanned Aerial System (sUAS) for journalists that is powerful, durable, transportable, affordable, upgradeable and supported by a community of experts.

Now one month into the project, development on “JournoDrone One,” or JD-1, is approximately 20 percent complete. DroneJournalism.org is working to secure funding to complete the project by the summer of 2012. The knowledge gained from making and using the drone for aerial photography will allow DroneJournalism.org to bring a similar system to journalists worldwide.

Leading the project is Matthew Schroyer, the founder of DroneJournalism.org, who holds a master’s in journalism from the University of Illinois. Mr. Schroyer has a background in engineering, experience with small, radio-control devices, and experience in using Geographic Information Systems (GIS) for data journalism purposes.

“We hope this is the first of many drones that DroneJournalism.org will develop,” he said. “It’s a practical exercise of existing off-the-shelf drone technology, and our first step into a frontier that could greatly expand public knowledge.”

Thursday, January 19, 2012

Learning from Crashing in Micro-Drone Journalism

If you are interested in getting started in drone

journalism, I highly suggest you first try a small, cheap, indoor RC

helicopter equipped with a low-resolution camera.

It will go up into the air, hit something, fall to the

ground. And the images will not be great. And sometimes it will just fall over

for no apparent reason. And you will fail.

Why choose to fail? Despite how

advanced our drone technology has gotten, despite the fact that you can program

a microcontroller to automatically fly your helicopter, you still need to

understand how things can shake out in the air.

This is my first-ever journalism drone, dubbed “the

JournoCopter” by my fiancée. It’s actually a toy called the “Hawk Eye,” and it’s

made by the Spinmaster company under the Air Hogs brand of remote-controlled flying

toys. They can be found for between $50 and $70 online, but I was fortunate

enough to locate this one on clearance at a Target for $41.

The micro-copter operates via a two-channel remote

control. That means there are two discreet frequencies that each control a

distinct flight characteristic. For this micro-copter, one of the channels is

the throttle for the rotors (makes it go up and down), while the other adjusts

the speed of the rotors to allow the helicopter to rotate and change direction

(left and right).

In addition to the sticks for throttle and direction on

the controller, there’s shoulder-mounted buttons for still-frame photography

and video. The helicopter can take more than a hundred photos at 640 x 480 (VGA

resolution), and about five minutes of video at 320 x 240 (QVGA resolution). To

get the photos and videos to a computer, the helicopter docks with the

controller, and the controller docks to a computer via USB cable (included).

Interfacing with the computer also charges the lithium-polymer battery in the micro-copter.

It takes about 25 minutes to charge the micro-copter’s lithium polymer battery

from USB.

How does it handle? It doesn’t so much handle as it

constantly drifts forward uncontrollably, leaving you to rotate the helicopter so

that it doesn’t run into anything. Flying it outdoors is a challenge, as this

small copter is influenced by the slightest of winds. And because this

micro-copter is controlled via infrared (IR) rather than radio control (RC),

much like a television is controlled by an IR remote, direct sunlight will

overpower the receiver and sever all communication.

Therefore, it’s best to fly it indoors. However, most

people don’t like to be confined in a room with a fast-spinning object that

they have no control over. Which brings me back to why this JournoCopter

failure is actually a good thing for drone journalism. By experimenting with a

small, cheap, finicky drone, you’re going to realize all of the little problems

that could manifest themselves as a big problem in a larger, more expensive

drone – because all of them will happen to you right from the start.

What do you do when the wind is too strong? How long do

you expect the battery to last, and how will you know before it’s too late? Do

you know how this flying object is going to behave? The limits of the flying

object? Where are the people, and how do you keep a safe distance from them while

still getting the shot? Because if worse comes to worse, you need to be

prepared to take control and land your drone without harming anyone. You’ll

learn these lessons while earning the fine motor skills that you’ll need to

pilot a wide variety of craft.

I don’t mean to denigrate this little wonder, either. For

less than $100, this company has managed to deliver a remote-controlled

helicopter with a two-mode camera, with onboard memory, that can actually fly.

Plus, it’s pretty damn indestructible.

But I would, actually, steer aspiring drone journalists

to spend just a little more money for a drone that has a smaller failure rate.

I cannot vouch for them, but this Egofly LT-712 Spyhawk and this Silverlit SpyCam cost a little more but might offer better control.

The International Journalists Network recently published

a list of the top “Five gadgets from CES that are ideal for journalists,” which

included two micro-copters for drone journalism. Those might also be worth

looking into.

Tags:

drone ethics

,

drone journalism

,

dronejournalism.org

,

journalism drones

,

UAV

Wednesday, December 14, 2011

Founding a Professional Society of Drone Journalists

It’s been quite a month for drones. After Iranian armed forces captured one of the coveted American RQ170 stealth drones, the very same stealth drone that pierced Pakistani airspace to spy on Osama bin Laden, Wired’s Spencer Ackerman released previously unpublished photos of the carnage that U.S. military drones unleashed in Waziristan.

Later, the Los Angeles Times wrote about how the U.S. Customs and Boarder Protection lent a Predator B drone to North Dakota law enforcement. Sheriffs in Nelson County, N.D., fearing a search for missing cattle would end with deadly firefight with a “sovereign citizen” group, spied on the group and arrested members after the drone revealed they were unarmed. The report went on to reveal that local law enforcement had used Predators stationed at the Grand Forks Air Base for at least two dozen surveillance flights since June, and the FBI and DEA have used Predators in their own investigations.

Salon’s Glen Greenwald warned of the expansion of domestic drones, and the sizable lobbying power of drone contractors in Congress, writing “the escalating addition of drones — weaponized or even just surveillance — to the vast arsenal of domestic weapons that already exist is a serious, consequential development. The fact that it has happened with almost no debate and no real legal authorization is itself highly significant.”

Meanwhile, the Washington Post dedicated its December 4 front page to the Israeli military’s use of drones in Gaza. But one Post reporter asked the question that journalists like me have been wondering for some time: What’s the potential use for drones in journalism?

Melissa Bell’s piece, “Drone journalism? The idea could fly in the U.S.” mentions my writing on a drone journalism Google group, where I mention that drone technology could help journalists “to take water or air samples or to scan for topographical data to make assessments about industrial impact on the environment.”

Bell mentioned Matt Waite, a journalism professor at the University of Nebraska – Lincoln and developer of Pulitzer Prize-winning Politifact, who just began the world’s first drone journalism lab. Waite unveiled his plan for a drone journalism lab at a News Foo conference, where the immediate reaction was skepticism.

“News Foo had a number of tech people very interested in and sensitive to privacy issues and they were quite wary,” Waite told data journalist Ben Welsh. “They immediately went to TMZ+Lindsay Lohan as an example of how drones could be misused.

“So when I started thinking about this idea, I immediately thought that people would rightfully be wary of this and that the sooner we started talking about ethics and laws, the sooner we could have answers for criticisms and guidelines to balance the public’s right to know and people’s expectations of privacy.”

I was unaware of Waite’s announcement, or his drone journalism lab, until the WaPo story. But given the most spectacular breach of journalism ethics in recent history (the News of the World/NewsCorp phone hacking scandal), it was not lost on me how important it would be to establish a code of ethics for drone journalists. The code of ethics would be deliberated and drawn up by experts in the field, similar to the way the Society of Professional Journalists developed and supported its code of ethics.

To that end, I purchased Dronejournalism.org as the future home of the Professional Society of Drone Journalists (PSDJ). At the time of this post, the website is dominated by a placard that displays the mission statement of the PSDJ: “Dedicated to developing the ethical, educational and technological framework for the emerging field of drone journalism.”

I also called Waite to bounce ideas about the first professional organization for drone journalists. One of his ideas was that the organization pursues a code of ethics via Wiki-style collaboration, but that the collaboration should only involve experts and practitioners of drone journalism. He, too, realized the need for an organization to help pull down a concrete ethical framework for journalists.

“This is really cool on one side, really creepy on the other,” Waite said in the conversation. “I think you are being dishonest if you are on the cool side, not thinking there’s something creepy about [drone journalism]. There’s a significant opportunity for mayhem and privacy violations.”

On the other hand, he said, “I think you are missing the point if you don’t see the amazing things you can do with the technology.”

For an example, Waite pointed out that Russian citizen journalists had employed an SLR-equipped drone to obtain aerial shots of a recent protest. The Daily Beast, one of the first news organizations to use a drone, surveyed tornado damage in Joplin, Missouri, and flood damage in Natchez, Mississippi and Minot, North Dakota.

Video from a citizen journalist capturing footage during Poland protests.

But there’s two other components to the PSDJ besides ethics: education and technology. We need to teach journalists how to use the equipment safely and effectively, and we need to keep journalists at the forefront of civil drone technology.

Waite used a $1,000 grant from the company he founded to purchase an off-the-shelf drone, the AR Drone quadcopter by Parrot, to be equipped later with a GoPro HD video recorder. Out of the box, the AR Drone provides a relatively stable platform for shooting video, and is controllable by iPhone or Android smartphone. Steve Doig, a Pulitzer Prize-winning data journalist who teaches at ASU, also is experimenting with the AR Drone platform.

"You can get it at Brookstone in the mall," Waite said. "It's got an API and you can hack it. It's made of stock parts. You can controll it from your smartphone. And it's cheap."

|

| A Parrot AR Drone in flight. |

The next step for me will likely be purchasing the same drone and outfitting it in the same fashion. Not too much later, I hope to be able to develop some Arduino-based, fixed-wing aircraft to shoot photos along a predetermined path, and stitch those photos together later. But Waite and I know this is just a starting point; an inexpensive, yet effective demonstration of the concept. From there, it’s experimentation and learning.

“What I would love to do, once we have these platforms, is let’s cover some news,” Waite said. “A house fire in your city. Spring floods. There will be tornadoes, it’s as predictable as the sun coming up. Let’s cover them and write about our experiences and through those.”

Subscribe to:

Comments

(

Atom

)